HAZOP in Practice: Identifying Critical Failure Paths to Enhance Process Safety

In many engineering projects, HAZOP has become a standard procedure. Teams conduct the sessions, fill out forms, complete reports, and archive everything. From a compliance perspective, there’s almost nothing to fault. Yet when an abnormality or accident occurs, a recurring question emerges: HAZOP was done, so why didn’t it prevent the risk?

Frontline engineers feel powerless because this isn’t necessarily negligence. Sessions are often thorough, with parameters, deviations, causes, and measures clearly documented. Still, once in operation, problems appear in unexpected places. Over time, HAZOP in many teams becomes a “compliance document” rather than a practical engineering tool.

In reality, HAZOP is not about producing a report but about identifying the few critical failure paths before an accident occurs and translating these concerns into design modifications and safety enhancements.

What HAZOP Actually Does

Accidents in complex industrial systems rarely occur suddenly. They evolve: assumptions from the design phase gradually deviate in operation, controls fail to stop the process, and eventually energy or material escapes. HAZOP exists to expose these deviations—often defaulted, ignored, or deemed “unlikely”—before they escalate.

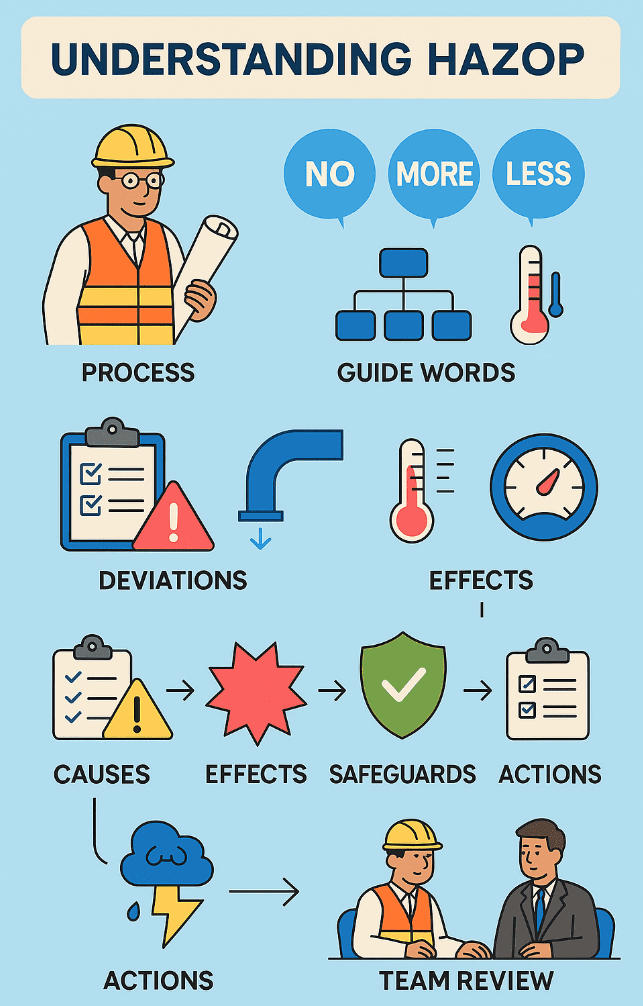

HAZOP stands for Hazard and Operability Study. Despite the literal meaning, beginners may misunderstand it as simply “finding hazards” or “preventing accidents.” In fact, HAZOP is neither accident analysis nor a hazard checklist. From an engineer’s perspective, it’s a structured method of testing whether the design intent holds by systematically introducing deviations.

The core of HAZOP is a structured review around design intent: if the system deviates from intended operation, can it still be controlled or safely blocked? By applying guidewords to key process parameters, the team identifies deviations, explores causes and consequences, assesses existing safeguards, and generates traceable recommendations for improvement.

Standards such as IEC 61882 and GB/T 35320 clearly require HAZOP to produce actionable, traceable recommendations, supporting engineering decisions rather than simply filling forms. Regulatory oversight in hazardous chemical projects emphasizes not just whether HAZOP is performed, but whether key scenarios are identified and effectively mitigated. This explains why accident reports often conclude that risk analysis was conducted, yet critical risks were inadequately addressed.

Why Many HAZOPs Are Superficial

The most common HAZOP failure is not “not doing it” but “doing it shallowly.” Typical manifestations include unclear design intent and generic deviations like “high temperature,” “low pressure,” or “no flow.” These forms may appear correct, but they lack actionable engineering information.

Engineers need to see failure pathways: does “high temperature” mean runaway heat, cooling failure, or sensor drift? Does “low pressure” indicate leakage, vacuum, or transient switching? If deviations don’t point to specific failure modes, causes quickly degrade to “operator error” or “instrument failure,” and consequences become “may lead to accident,” often ending with recommendations like “increase training” or “enhance inspection.” The form is complete, but critical failure paths remain unclear.

Guidewords are just tools. HAZOP’s real value lies in forming a complete deviation–cause–consequence–protection–recommendation chain and proposing implementable, verifiable risk reduction measures.

Consequence Analysis Must Support Decisions

HAZOP isn’t quantitative risk assessment, but consequence analysis must reach the engineering judgment level. It should inform decisions like entering LOPA/SIL studies or implementing inherently safer design. Consequences should describe released energy or materials, magnitude, affected range, evolution speed, and whether human intervention is feasible. Rapidly evolving, non-intervenable scenarios cannot rely solely on operators as the primary risk control.

Regulators increasingly scrutinize whether consequences are specific and based on real operational scenarios, because accidents show that risks often aren’t blocked not due to underestimating severity, but because the severity, scope, and operability were unclear.

Protection Layers Must Be Reliable Barriers

Protection measures are often overestimated. Procedures, training, and inspections are necessary management measures, but rarely serve as independent, reliable technical barriers.

Accident scenarios evolve rapidly with incomplete information, so relying on correct human intervention is inherently uncertain. Many projects discover only at LOPA or SIL stage that supposed protection layers are neither independent nor verifiable, necessitating rework.

A valid protection layer must answer four questions: independent of the cause, automatic in action, with defined function and trigger, and verifiable (inspection, interlock tests, calibration). If bypass exists, its management must also be evaluated.

HAZOP for Reactors

For reactors, the depth isn’t “temperature high/low,” but whether heat can be removed, the system remains within limits, and controls and protections avoid common cause failures. First, clearly define design intent, including target temperature and pressure ranges, heat transfer paths and capacity, critical control loops and interlocks, and maximum allowable temperature/pressure. With intent clear, deviations can be compared to specific exceedance criteria.

Deviations should reflect failure modes, e.g., cooling failure leading to heat accumulation: insufficient or interrupted cooling water, stuck control valves, fouling reducing heat transfer, or sensor errors causing control distortion. Consequences must include rapid pressure rise, PSV action, material release, and evolution risks without human intervention.

Other overlooked paths include agitation or mixing failure causing local hotspots. Even if overall temperature seems normal, local concentrations may trigger runaway reactions. High-risk deviations also include composition errors: wrong feed, overfeeding, or incorrect sequence leading to heat peaks beyond design transfer capacity. If attributed only to “operator error,” structural improvements are missed.

Protection layers must account for common-cause failures, e.g., control and interlock sharing the same sensor, DCS power/network shared with interlock, interlocks bypassable, or PSV not verified under upset conditions. Reliable layers include high-high interlocks cutting feed and maximizing cooling, independent SIS sensors, and venting/treatment systems verified for upset scenarios.

HAZOP for Storage Tanks

Tank HAZOP cannot be superficial. Design intent must include receiving/dispatch operations, boundary conditions, material properties, fill/empty sequences, liquid level/pressure/vacuum limits, breathing system, bunds, foaming, alarms, and interlocks.

High-level deviations should be written as overflow failure modes: continuous filling exceeding safe levels, liquid spilling, pooling in bunds with combustible vapor. Causes must be system-level: level transmitter error, wrong cut-off logic, uncommissioned high-high interlock, or pump failure. Consequences must cover vapor clouds, ignition sources, and toxicity exposure.

High-pressure deviations must consider breathing system failures: blocked or poorly maintained vents/flame arresters, causing overpressure, tank deformation, seal failure, and release. Vacuum deviations may occur from excessive outflow or temperature drop causing air ingress and explosive mixtures.

Protection judgment focuses on whether high-high level can truly “stop” the process. Alarms alone do not block. Effective barriers include independent LSHH triggers stopping pumps and closing feed valves with fail-safe design, regular testing, and bunds for mitigation, with closed drain valves. Gas detection serves only as a discovery layer unless linked to automated cutoff.

Conclusion

HAZOP’s outcome is not filling forms; it is forming traceable failure path knowledge and verifiable risk reduction measures. A practical standard to evaluate HAZOP effectiveness: whether critical failure paths at key nodes are identified and lead to substantive changes in control boundaries, interlocks, or inherently safer design. If not, the analysis remains merely formal.