The Limitations of Guided Radar vs Non-Contact Radar Level Measurement

Radar Technology in Industrial Level Measurement

In industrial level measurement, radar technology has reached a high level of maturity.

Across petrochemical, chemical, energy, and water treatment industries, radar level measurement has almost become the “default choice.”

Yet in real engineering projects, one practical question repeatedly arises:

Why are some applications better suited for guided radar, while others insist on non-contact radar level transmitters?

Explaining this difference simply as “contact vs non-contact” is often insufficient to support real engineering decisions.

In fact, guided radar and non-contact radar are not in a simple replacement relationship.

They address two fundamentally different types of uncertainty, based on different measurement assumptions. As a result, each technology is valid within its own boundary—and limited beyond it.

Level Measurement Is Not Merely “Measuring”

In industrial environments, liquid level is rarely a clean, stable, or well-defined geometric interface.

Any level measurement is essentially a negotiation with uncertainty, mainly in three dimensions:

- Interface uncertainty

Foam, emulsification, turbulence, and vague phase boundaries make the “liquid surface” itself unclear. - Propagation path uncertainty

Vapor, dust, pressure variations, and internal tank structures make signal propagation unpredictable. - Sensor condition uncertainty

Condensation, buildup, crystallization, and aging alter the sensor’s effective operating conditions.

The fundamental difference between guided radar and non-contact radar lies not in which technology is more advanced, but where each technology places these uncertainties.

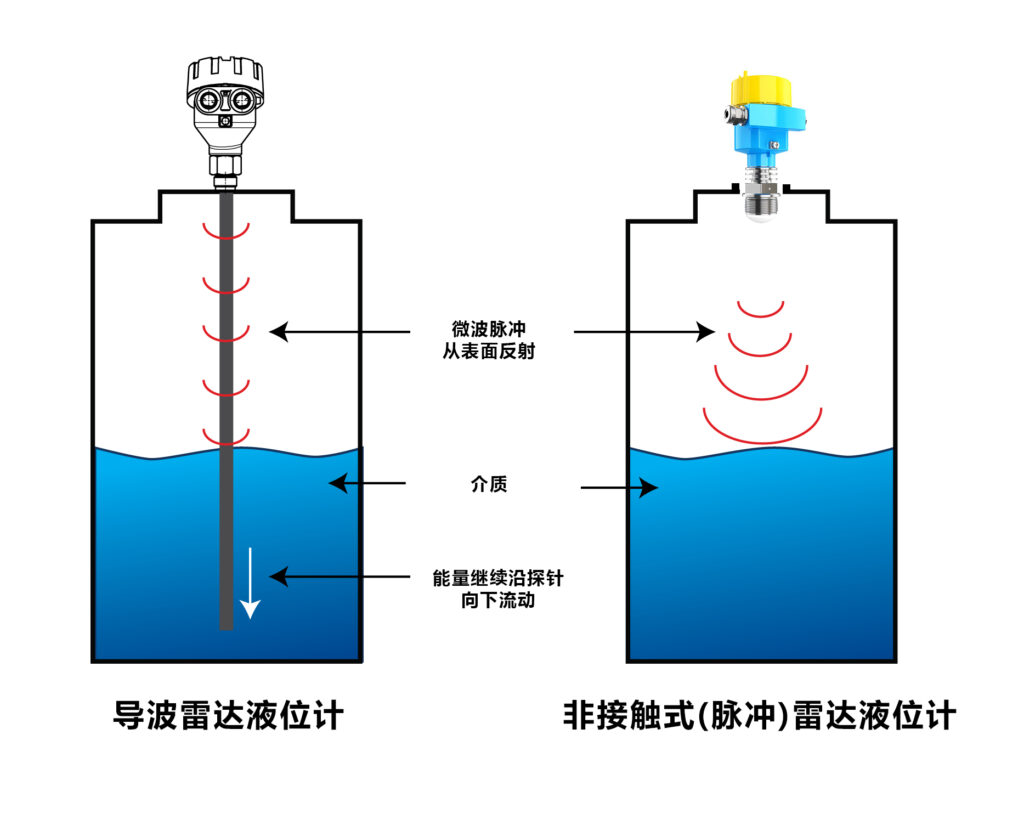

Non-Contact Radar Level Transmitters

Non-contact radar level transmitters emit microwave signals downward through an antenna.

The electromagnetic wave travels through the vapor space, reflects off the liquid surface, and returns to calculate level.

Their advantages are well established:

- Completely non-contact, avoiding corrosion, adhesion, and contamination

- Suitable for high temperature, high pressure, and highly corrosive media

- Capable of very long measuring ranges, ideal for large tanks and spheres

- No mechanical risks such as probe deformation or buildup over long-term operation

For these reasons, non-contact radar is nearly irreplaceable in applications such as crude oil tanks, refined product storage, and large vertical chemical vessels.

However, all these advantages rely on an implicit assumption:

The liquid level must be a clearly identifiable electromagnetic target in free space.

When this assumption breaks down, challenges emerge rapidly:

- Vapor density changes cause attenuation and refraction

- Foam and dust introduce scattering and false echoes

- Agitators, coils, and internals generate strong reflections

- Severe surface agitation leads to unstable echoes

In such conditions, radar does not necessarily “fail,” but becomes highly dependent on signal processing algorithms, echo discrimination strategies, and engineering experience to identify the true level.

Guided Radar

Guided radar follows a fundamentally different measurement logic.

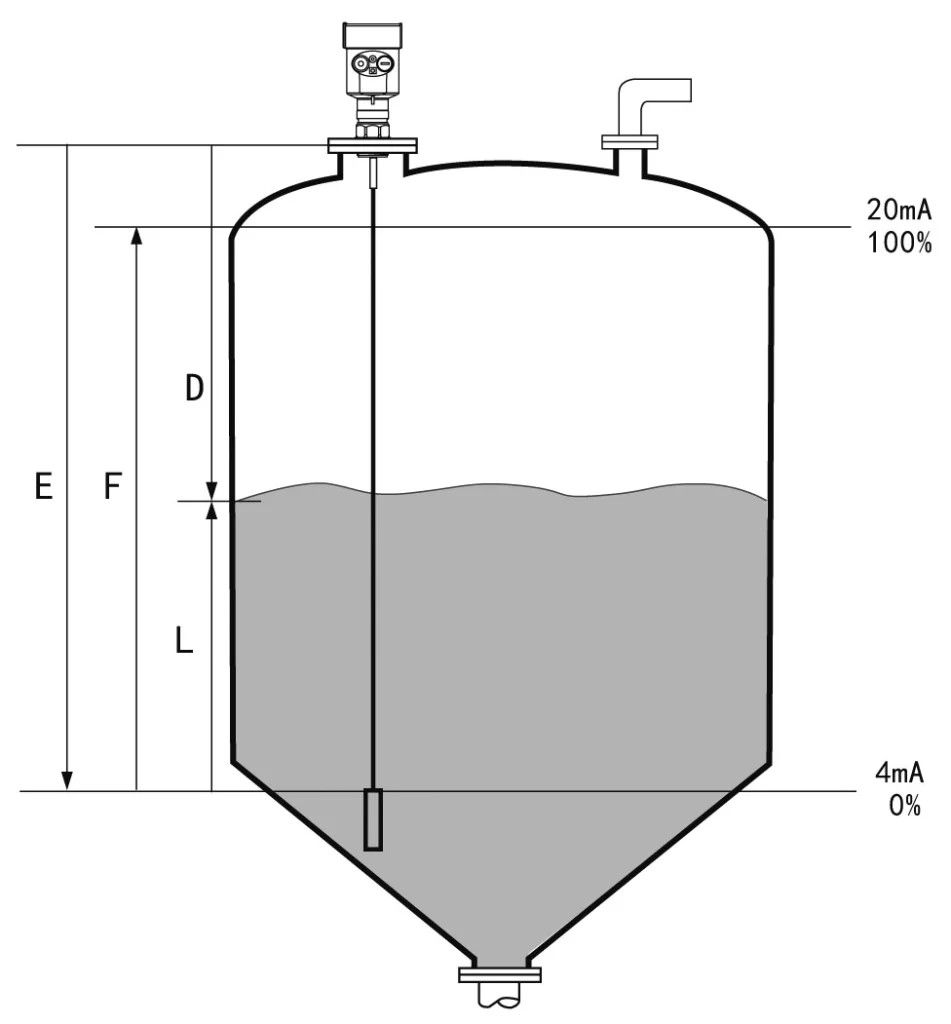

Instead of allowing electromagnetic waves to propagate freely in the vessel, the signal is guided along a probe or cable, constraining the propagation path. This directly reshapes how uncertainty is distributed:

- Signal path is fixed, greatly reducing spatial environmental influence

- Minimal sensitivity to vapor, foam, or dust

- Easier detection of low dielectric media due to higher coupling efficiency

- More stable echo structure, supporting repeatability and trend control

As a result, in applications with complex internal structures, strong vapor interference, or weak surface reflectivity, guided radar often captures a stable signal more easily.

This stability, however, comes at a cost.

By design, guided radar achieves robustness through direct contact with the medium—introducing its own limitations:

- Probes may suffer from buildup, crystallization, or polymerization

- High-viscosity media may coat the probe, dulling reflections

- Strong mechanical vibration or level surges affect cable stability

- Structural and installation constraints become significant in very large tanks

In other words, guided radar reduces spatial uncertainty, but increases sensitivity to sensor surface condition.

Dielectric Constant Is Not About “Measurable or Not”

In engineering discussions, dielectric constant is often simplified as a threshold of “measurable or not.”

In practice, it primarily affects measurement margin and stability.

- For non-contact radar, low dielectric constants mean weak reflections. When combined with vapor or foam, echoes may easily be overwhelmed.

- For guided radar, low dielectric constants also reduce reflection strength, but concentrated energy and efficient coupling often maintain detectable signals.

This does not mean guided ave radar is immune to dielectric effects.

Rather, it reframes the question as:

Can a stable impedance discontinuity be formed along the guided path?

Interface Measurement

In processes such as oil–water separation, extraction, and settling, interface level is a critical control variable.

When the dielectric contrast between upper and lower phases is sufficient, guided radar can generate multiple reflections at the gas–liquid and liquid–liquid interfaces, enabling simultaneous level and interface measurement.

This capability, however, is not automatic. It depends on:

- Adequate dielectric contrast between phases

- A clear and stable interface

- Probe placement covering the interface variation range

In cases of severe emulsification or blurred phase boundaries, radar—or alternative measurement methods—may be more appropriate.

Different Priorities in Interference Resistance

An often-overlooked but critical reality is:

- Non-contact radar is primarily affected by spatial conditions

- Guided radar is primarily affected by sensor surface condition

As a result, their “interference resistance” cannot be compared in absolute terms.

In reactors with dense vapor, heavy foam, and complex internals, non-contact radar echo identification becomes significantly more challenging.

Conversely, in media prone to crystallization, adhesion, or polymerization, guided radar may evolve into a long-term maintenance concern.

Conclusion

From a lifecycle perspective, each technology excels at solving different problems:

- In clean, large-scale vessels with strong non-contact requirements, non-contact radar offers superior long-term reliability.

- In spatially complex environments where signal stability is the priority, guided radar is often easier to keep under control.

Engineering selection is never about “whether it can measure today,” but whether its long-term failure modes are acceptable.

When operating assumptions are satisfied, technological advantages become evident.

When those assumptions are violated, even the most advanced instruments struggle.

Understanding this matters far more than memorizing “when to choose guided radar or non-contact radar.”