Why EMC Determines the Measurement Stability of Radar Level Meters in Industrial Environments

In industrial applications, feedback regarding the anti-interference performance of radar level meters is not uncommon. For example:

- “The radar level meter shows periodic signal jumps near the variable frequency drive.”

- “Liquid level readings shift significantly at the moment the motor starts.”

- “Under the same installation and operating conditions, measurement stability varies significantly between different brands.”

Many users tend to attribute these phenomena to “insufficient algorithms” or “radar inaccuracy.” However, in strong electromagnetic interference (EMI) environments, the vast majority of measurement anomalies are not caused by the measurement principle or algorithm precision, but by insufficient EMC (electromagnetic compatibility) capabilities. As highly sensitive RF measurement devices, radar level meters have very weak echo signals and limited frequency ranges, making their front-end circuits and signal processing chains extremely susceptible to external electromagnetic noise. Even minor interference can affect the system’s signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and echo recognition stability, resulting in measurement drift.

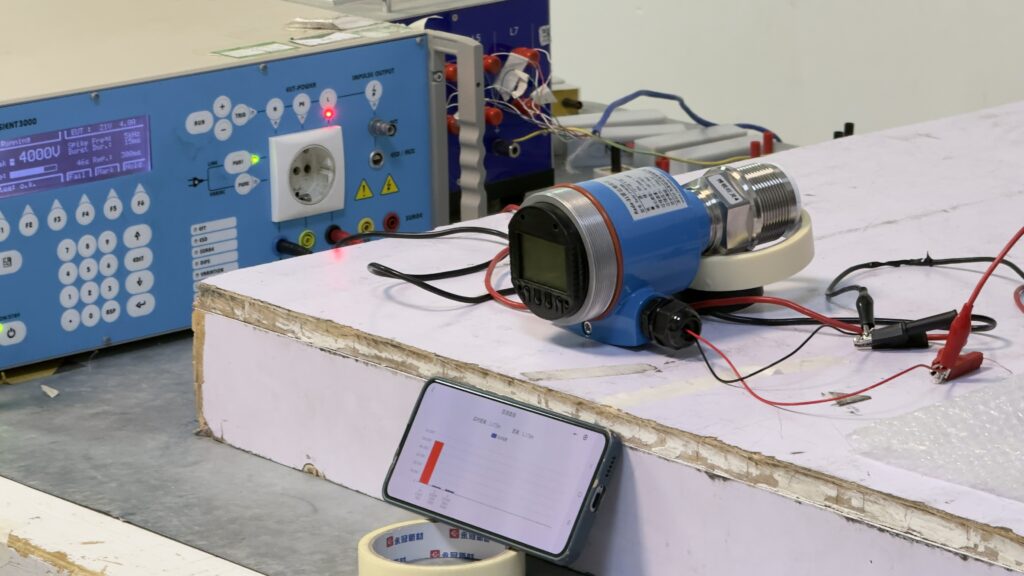

Taking Jiwei radar level meters as an example, these products undergo strict EMC testing before leaving the factory, including radiated, conducted, and transient immunity verification, to ensure stable measurements in complex industrial electromagnetic environments.

Jiwei radar level meters are rigorously tested for the full range of EMC performance, covering radiated, conducted, and transient immunity, to ensure stable operation under complex industrial electromagnetic conditions.

This article will analyze, from both engineering and EMC design perspectives, the formation mechanisms of interference sources, why radar level meters are particularly sensitive to interference, and how EMC performance fundamentally determines measurement reliability and long-term stability.

01. On-Site Drift Is Not “Inaccuracy,” but “Interference”

In normal environments, radar measurements are very stable. However, once installed near variable frequency drives, motors, welding machines, solenoid valves, or high-power power distribution equipment, the liquid level curve may show jumps or discontinuities. The liquid level is not actually fluctuating; rather, the radar is passively receiving additional energy from the environment, causing the true echo to be masked by noise.

Radar level meters essentially operate by “listening for extremely weak echoes in a noisy environment.” The stronger the ambient noise, the more the radar resembles someone trying to hear a whisper in a noisy marketplace, making interference frequent and unavoidable.

02. How Strong Interference Enters

Interference in industrial sites primarily enters via three paths: radiated, conducted, and transient. The combination of these forms constitutes the main threat to radar stability.

- Radiated interference comes from variable frequency drives, motors, welding machines, and high-frequency equipment, which emit substantial RF energy into the air. The radar antenna inherently acts as an RF receiver, and the more stray energy in the environment, the more likely the antenna is to interpret interference as a valid echo.

- Conducted interference enters the radar via power and signal lines. When a VFD or motor starts, sharp high-frequency pulses can be introduced into the power system. If the radar lacks sufficient isolation or filtering, these disturbances propagate directly into the signal processing chain, causing output fluctuations, ADC jitter, or communication instability.

- Transient interference, such as ESD, surge, and EFT, can impact the circuitry for microseconds. Although brief, such impulses can cause the MCU or amplifiers to malfunction momentarily, resulting in instantaneous measurement interruptions.

Many “instantaneous jump points” observed in the field are not actual liquid level changes, but short-term functional failures caused by transient electromagnetic interference. Such interference temporarily disrupts the RF front-end, signal conditioning chain, or control processing unit, preventing stable echo extraction and appearing as sudden measurement deviations.

03. Why Radar Is More “Fragile” Than Other Instruments

Compared to mechanical magnetic floats, float switches, or instruments based on differential pressure or ultrasonic measurement, radar level meters are more prone to “signal drift” or intermittent instability. This is not because other instruments are intrinsically more reliable; rather, their operating principles are largely immune to electromagnetic disturbances. For example, magnetic floats rely entirely on buoyancy and mechanical transmission and cannot be affected by EMI; differential pressure and float switches mainly respond to hydrostatic forces; ultrasonic devices are affected by environmental noise but have stronger signal amplitude and higher interference tolerance than millimeter-wave radar.

The reason radar is more sensitive in strong interference environments is that millimeter-wave echo power is extremely low. Detection relies heavily on extracting and discriminating weak reflected signals, making SNR highly susceptible to electromagnetic noise.

This is particularly true for 80 GHz near-field high-frequency radar. Although it offers advantages in complex conditions such as vapor, dust, and agitation, its RF front-end sensitivity is higher, detection thresholds lower, and internal high-speed digital and RF circuits more precise, increasing the importance of EMC for overall stability.

Academically, radar measurement stability is governed by SNR, which is directly affected by electromagnetic noise, power quality, transient pulses, and RF coupling. Therefore, radar relies on EMC design significantly more than mechanical or hydrostatic instruments.

In short: radar does not “drift” per se, but in weak-signal mechanisms, it exposes the true electromagnetic environment.

04. EMC Affects the Entire Measurement Chain

Superior EMC capability is not merely about passing standard tests. It fundamentally determines the radar’s signal acquisition, output stability, communication reliability, and long-term operational lifespan.

Jiwei radar level meters undergo comprehensive EMC testing during development, including radiated, conducted, and transient immunity, with systematic optimization from signal chains and RF front-end to power filtering, ensuring stable and reliable operation in complex industrial environments.

- Echo recognition: If interference exceeds the radar’s EMC design margin, weak real echoes may be masked by noise, preventing the signal processing algorithm from accurately tracking the liquid surface. This may present as false peaks, reduced SNR, or measurement jumps, causing discontinuous or fluctuating level curves.

- Output stability: 4–20 mA analog loops are often assumed to be “interference-proof,” but in low EMC designs, the current loop fluctuates with external interference, resulting in slow drifts or abrupt jumps. The observed variation is not real liquid level change, but interference-driven signal.

- Communication reliability: In high-interference environments, HART or Modbus communications may experience CRC errors, packet loss, or interruptions. Low-EMC radars may frequently disconnect during configuration or commissioning, affecting accurate control and data acquisition.

- Long-term durability: Low EMC margin means the instrument continuously experiences stress from interference, accelerating component aging. Some low-cost radars operate normally initially, but develop frequent anomalies after six months, typically due to cumulative EMC-related damage.

Overall, EMC level not only impacts short-term measurement stability but also long-term reliability and lifespan, making it a critical consideration for design and selection.

05. Why Some Radars Are Stable While Others Drift

Different brands of radar exhibit significant differences in EMC design. Factors include whether shielding is continuous, antenna-to-housing grounding, power filter specifications, RF front-end interference margin, and PCB layout reserved for EMC considerations.

These details are usually invisible and not listed in datasheets, but their impact is immediately apparent in high-interference environments. Stable radars often appear ordinary externally, but their internal EMC design effectively suppresses interference. Less stable products may have attractive datasheets but lack resistance under real-world interference, resulting in poor measurement accuracy and reliability.

06. Conclusion: EMC Is Not a Selling Point, but Core Competence

The measurement stability of radar level meters in high-interference industrial environments fundamentally depends on whether they can reliably acquire and process true echoes in complex electromagnetic conditions—not on appearance, algorithm marketing, or frequency band.

High-EMC radars maintain continuous measurement, stable output, and uninterrupted communication even near VFDs or during frequent motor start-stop cycles, without accumulating long-term faults.

Conversely, devices with low EMC margins are highly environment-dependent: measurements become unstable near interference sources, anomalies occur in complex conditions, and potential risks increase over time.

Therefore, EMC is not an optional feature; it is the foundational capability that determines measurement reliability, stability, and long-term value of radar level meters.